Can You Return An Animal To A Shelther

Abstruse

Unsuccessful animal adoptions are stressful for many owners and may reduce their willingness to adopt again. The goal of this written report was to determine the proportion of return owners who adopted post-render and investigate render characteristics that affected the likelihood of post-return adoption. We analyzed adoption records from a Southward Carolina animal shelter between 2015 and 2019 (n = 1999) using a logistic regression model including postal service-return adoption (binary) and return reason, species, animal sexual practice and age. We found ane in 10 individuals adopted from the shelter within 12 months of return, and post-return adoption was associated with return reason and species. Returns due to owner-related reasons, such as the owner's wellness (OR 0.twenty, 95% CI 0.07, 0.57) or unrealistic expectations (OR 0.42, 95% CI 0.19, 0.94) were associated with significantly lower odds of post-return adoption. Owners who returned due to the beast's wellness exhibited 4 times greater odds of mail-return adoption compared with behavioral returns (OR 4.20, 95% CI 2.37, seven.45). Our findings highlight the value of ensuring adopters' expectations are aligned with the reality of buying and minimizing adopter-animal behavioral incompatibility as unsuccessful animal adoptions can reduce the possessor'south willingness to adopt again and may touch on the adopter's relationship with the shelter.

Introduction

Pet ownership is popular in the United States with 57% of U.Due south. households estimated to own a pet. Dogs are the most common companion beast and tin can exist establish in 38% of U.Southward. households, while 25% of U.Due south. households are cat ownersone. Approximately 3.two million animals are adopted from brute shelters each year, and recent reports suggest adoption from an creature shelter is typically the preferred method of pet acquisition amidst prospective ownersii,3,4. Garrison and Weiss4 found more than than 80% of prospective dog owners considered acquiring their dog from a shelter. Even so, animals are returned to the shelter post-obit adoption in 7% to 20% of all adoptionsv,6,7,viii,9,10,11. Returns occur for a multifariousness of reasons, although animal behavior has been consistently documented as a chief cause of return for both dogs and cats6,7,viii,eleven,12. Incompatibility with existing pets and possessor's health concerns, particularly allergies among cat adopters, also lead to a pregnant number of returned adoptionsxi,12,13.

A considerable torso of enquiry has investigated the furnishings of the shelter environment on beast health and wellbeing14,15,16,17,18, merely the effects of pet relinquishment on owner wellbeing has received less scientific attention. In a report of relinquishing owners, DiGiacomo et al.19 reported all participants found the decision to give up their pet very difficult. In the only study to date to investigate owners' perceptions of returning a newly adopted beast, Shore20 institute most owners thought the experience was very difficult. Twoscore-ane percent of returning owners indicated they would not adopt a pet in the time to come and a further thirteen% were unsure whether they would adopt again20. These data suggest unsuccessful fauna adoptions may detrimentally affect individuals' desire to own a companion animal in the time to come, although no empirical evidence exists to back up this hypothesis.

The unsuccessful animal adoption experience is likely to vary for each homo-animal dyad which could differentially affect the likelihood of owners adopting again post-return. For example, Shoretwenty found that some returning owners indicated they would not prefer again—e.g., one adopter whose child was allergic to the pet—while others indicated they would adopt a dissimilar animal in the future, such as an adopter whose landlord had a pet weight limit which prevented her from keeping the pet20. To our knowledge, the effect of return characteristics on the odds of post-return adoptions has non yet been investigated. The aims of this study were to investigate the rate of post-return adoptions at a big animate being shelter in the Southeastern Us, and to decide whether characteristics of unsuccessful animate being adoptions affect the likelihood of post-render adoptions.

Results

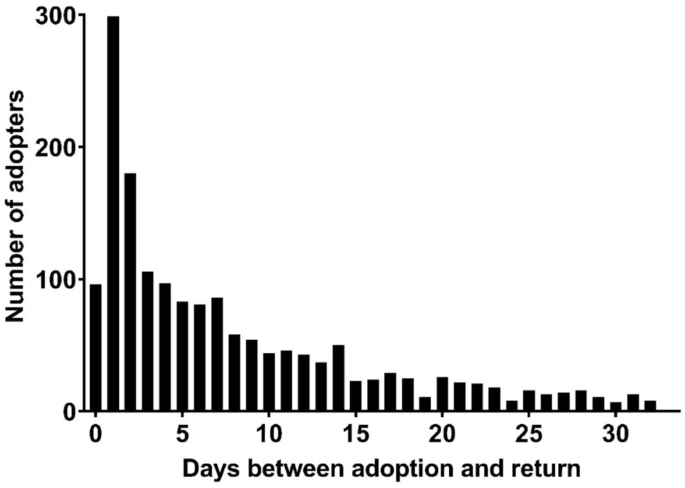

A 5-year retrospective analysis of adoption records from Charleston Animal Society (South Carolina, United states of america) showed 1999 owners returned animals to the shelter following adoption, giving an overall render rate of 9.2%11. The vast bulk of individuals returned one fauna (n = 1899, 95.0%), although 4.four% returned ii animals (due north = 88), 10 adopters returned three animals and two adopters returned iv animals. Individuals who returned more one animal during the study catamenia were excluded from further analyses (n = 100). Cases where more than two animals were adopted prior to return were as well excluded from the logistic regression models (n = 214). The returned animals included 1486 dogs, 402 cats, ix rabbits and ii barnyard animals. The hateful length of ownership was 8.68 days (SD 16.70, Fig. 1).

Length of adoption (days) for animals returned inside i month (n = 1666).

The characteristics of the returned animals, the reasons for return and the animals' outcomes post-return have been described in detail elsewhere11. In brief, nigh returned animals were adults (38.2%), 28.6% were young adults, xiv.1% were under the age of half dozen months and iii.8% were seniors. The majority of returns were as well male (54.nine%). Behavior was the most common return reason accounting for 32.eight% of returns, followed by incompatibility with existing pets at 21.5% and owner circumstances at 11.ii%. Return reasons differed between dogs and cats (X 2 = 138.54, p < 0.001). Post-hoc analyses using standardized residuals showed dogs were returned more frequently than cats for beliefs (36.one%) and housing problems (11.3%), and cats were returned more than due to the health of the owner (17.8%) and the health of the beast (nine.8%). The detailed render reasons are provided in Tabular array i.

Post-return adoptions

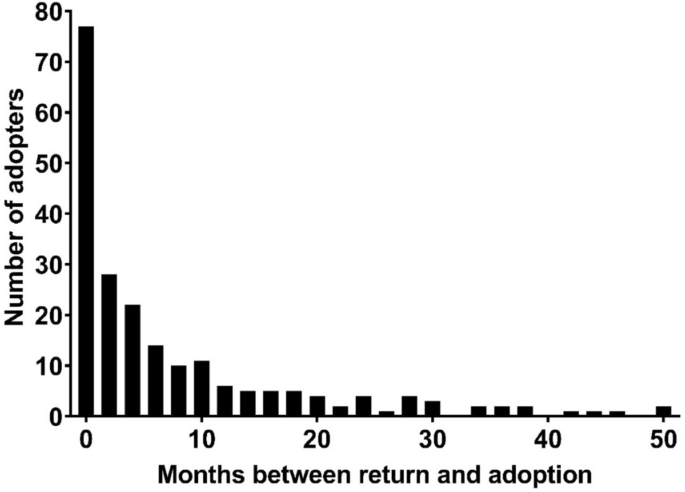

ten.five% of return owners adopted a new animal following render, including 144 individuals who returned dogs, 65 individuals who returned cats and 1 individual who returned a rabbit. The median length of time between return and mail-adoption return was 3.2 months (Fig. ii), with no difference between cat and dog returns (t(207) = 1.24, p = 0.22). The adopted animals included 107 dogs, 101 cats, one rabbit, and i guinea squealer.

Months between return and adoption post-render for all owners who adopted a new brute during the written report menstruum (due north = 210).

A binary logistic regression model revealed the likelihood of post-render adoption within 12 months was associated with species (including cats and dogs only). Individuals who returned cats were ii.45 times more likely to prefer a new animal compared with individuals who returned dogs (OR 2.45, 95% CI i.62, 3.72). The reasons for return were likewise associated with the likelihood of post-return adoption. Owners who returned animals due to the animate being's wellness were four times more likely to adopt a new animal compared with owners who returned animals for behavioral reasons (OR iv.20, 95% CI 2.37, seven.45). Owners who returned animals due to their personal wellness or circumstances were 80% and 59% less likely to adopt another animal compared with owners who returned animals for behavioral reasons (OR 0.20, 95% CI 0.07, 0.57 and OR 0.41, 95% CI 0.20, 0.82). 'Unrealistic expectations' and 'not compatible with pets' were besides associated with decreased odds of mail-render adoption compared with returns due to behavioral reasons (OR 0.42, 95% CI 0.19, 0.94, and OR 0.61, 95% CI 0.38, 0.98). Returns due to incompatibility with the possessor or children, housing problems, or 'unwanted' were non associated with the likelihood of postal service-return adoption (p ≥0.xiv). Length of stay in the home (p = 0.89) and the sex (p = 0.88) of the returned animal did not predict the odds of postal service-return adoption. The likelihood of post-render adoption was too not significantly associated with the returned animal'south age grouping, although there was a tendency towards an increased likelihood of postal service-return adoption amidst developed animals (OR 1.61, 95% CI 0.95, 2.72, p = 0.08).

Characteristics of mail-return adoptions

Most owners adopted the same species mail-render (75.7%, n = 159), but 24.3% adopted a dissimilar species (due north = 51). Of those who adopted a different species, 84.3% adopted a domestic dog initially and and so adopted a cat post-render (n = 43), whereas thirteen.seven% adopted a cat initially and then adopted a dog postal service-return (n = 7). One individual returned a canis familiaris and so adopted a rabbit. Considering individuals who adopted the aforementioned species post-return, virtually half adopted an brute of a unlike sex post-return (43.4%, n = 69), although the management of change was split. Thirty-two owners returned a female and and then adopted a male beast post-return, and 37 owners returned a male and and then adopted a female post-return. Almost returning owners adopted from the aforementioned age group mail service-return (84.8%, n = 178). All owners who adopted an animal of a dissimilar historic period grouping chose an older animal postal service-return (n = 32).

Word

To engagement, the bear on of unsuccessful animal adoptions on the likelihood of owners adopting a new creature post-return has not been established. At this large animal shelter in the Southeastern United States, one in 10 individuals adopted a new beast from the shelter post-return suggesting the unsuccessful adoption experience decreased adopters' desire to acquire another pet from the shelter. The majority of individuals who adopted again did non change their animate being preferences mail-return with the exception of sexual practice, whereby half of returning owners adopted an animal of a different sex following return. Nosotros too institute i quarter of individuals adopted a different species following return, most of whom returned a canis familiaris and adopted a cat. It is possible that individuals who returned dogs were more inclined to adopt cats post-render due to the lower perceived costs and responsibilities of cat ownership compared with dog ownership21.

The reasons for return had a meaning influence on the likelihood of future adoptions. Owners who returned animals due to the animal's wellness were four times more than likely to adopt post-return compared with owners who returned animals for behavioral issues. Behavior problems have been associated with greater ownership costs22,23,24, decreased buying satisfaction23, decreased man-beast attachment25 and poorer mental wellbeing among owners24,25,26. In dissimilarity, compatibility between owners and their pets on key behavioral characteristics, such as enjoying exercise and getting forth with peers, has been associated with greater ownership satisfaction and happiness, and decreased stress27,28. Research also indicates that caring for an animal with medical needs tin can increase stress and anxiety and reduce owners' quality of life29,xxx,31. It is therefore interesting that returns due to animal behavior had such a detrimental upshot on the likelihood of hereafter adoptions compared with medical concerns. It seems a mismatch between the animal's behavioral needs and the owner's willingness to tolerate behavioral issues could damage the adopter's long-term relationship with the shelter. Considering that behavior is a leading cause of post-adoption returns6,7,11,12, it is imperative that animal shelters aim to minimize behavioral incompatibility between adopters and their animals. The efficacy of adoption counselling and adopter-animal matching programs in reducing returns is a developing area of enquiry that warrants further attention. Preliminary evidence suggests some policies, such equally but showing adopters the animals that match their needs, may be associated with reduced return rates but additional inquiry is needed32.

Individuals who returned animals for owner-related reasons were considerably less probable to adopt post-return. For example, owners who returned animals due to their health or the health of their family were 80% less probable to adopt again. This finding is logical as health concerns that are exacerbated past pet ownership, such as allergies, may not improve with the introduction of a different pet. Previous research has constitute owners who relinquished animals due to allergies often viewed their state of affairs equally insurmountable19. Returns due to owners' circumstances were besides associated with a lx% reduction in the odds of hereafter adoptions. Once more, owners' circumstances, such equally personal problems or a lack of time, may not improve with the introduction of a dissimilar pet.

Returns due to unrealistic expectations for ownership were associated with a 60% reduction in the likelihood of futurity adoptions. Ownership satisfaction has been shown to decrease with greater perceived costs of ownership, including lifestyle, time, and financial costs23. Adopters who underestimated the attempt involved in caring for an animal may accept been dissatisfied with pet ownership and therefore, less motivated to adopt again mail service-return. It is besides possible that some owners had unrealistic expectations for benefits attributable to pet ownership. Previous research indicates that individuals with canis familiaris ownership history (previous or current owners) are more likely to expect mental and psychosocial health benefits than prospective owners with no prior experience, possibly due to bias arising from their amore towards their previous/current dog33. Data regarding the influence of previous ownership history on the risk of returns is mixed. One study found adopters with previous ownership feel returned animals more often due to behavioral problems than starting time-time ownersvi, but other studies have found beginning-time owners are more likely to return animals9. A lack of data regarding adopters' lifetime pet buying history precluded us from investigating the role of previous pet ownership on post-return adoptions in the current study. Incompatibility with existing pets was too associated with xl% lower odds of mail-return adoption, suggesting that some owners concluded they did not want to upset the current pet dynamic or that their electric current pet was better suited as the merely pet in the household.

Individuals who returned cats were 2 and a one-half times more than likely to adopt post-render compared with domestic dog adopters. This finding may be attributable to the differences in render reasons betwixt dogs and cats, such equally the higher charge per unit of cat returns due to the animal'south health. True cat and dog adopters may also differ in their expectations for ownership which could affect the likelihood of owners adopting mail service-returnnine,34,35. For instance, preliminary data suggests cat owners believe their ability to control or modify their true cat's behavior is depression36,37, while nigh dog owners anticipate the need for training and wait to meet some difficulties with canis familiaris behavior33. Cat adopters that experience undesirable beliefs may believe the behavior cannot exist modified and that a different cat would be meliorate suited to their household. Alternatively, domestic dog adopters that confront difficulties with behavior may feel information technology is their responsibility to work with the canis familiaris to modify its behavior. If the beliefs is too challenging for the adopter, resulting in the creature'due south render to the shelter, the owner may question whether they have the time or resources necessary for dog ownership. It is likewise possible that individuals who returned dogs to the shelter may have acquired a dog from a different source post-return. Future studies might focus on the differences in adopters' expectations of ownership based on species and their role in mail service-return adoptions.

Length of stay in the home was non associated with the odds of future adoptions. The mean length of ownership in this report was relatively short, and it is possible that the provision of adoption vouchers for returns within thirty days incentivized adopters to return the animal within this period. Even so, this does not explicate the significant number of returns that occurred inside the first week of ownership. Information technology is besides plausible that adopters observed the problem that led to return relatively rapidly after bringing the animal home. Previous work has found one-half of returning adopters observed the problem that led to return immediately after adoption, and a further 17% observed the problem within the showtime calendar week20. The brusque length of buying may have limited differences in the force of the human-creature bond, peradventure reducing any impact of length of ownership on the likelihood of readoption. Nosotros also found the sex of the returned animal was not associated with the likelihood of post-return adoption.

The findings presented in this study are bailiwick to several limitations. Firstly, the data reflect a single animal shelter and inquiry across multiple facilities is needed to ostend our findings. The retrospective nature of the study also necessitates cautious interpretation. For example, we could non establish how many owners, if whatsoever, had acquired pets through alternative sources, then the true charge per unit of pet conquering following unsuccessful creature adoptions may exist significantly higher than suggested here. Nevertheless, our findings speak to the importance of the unsuccessful adoption experience on individuals' willingness to adopt from the same animal shelter and betoken potential long-term effects of returns on the shelter-adopter relationship. The retrospective design also resulted in a reliance on owner-reported return reasons which may be subject to bias or inaccuracies38,39. For case, returns due to behavioral issues are likely affected by the owner'southward understanding of animal behavior, and previous research suggests owners' power to recognize animal behavior is poor40,41,42. However, given that this written report focused on the owner-related effects of unsuccessful beast adoptions, the possessor's perceived render reason is important irrespective of the accuracy of the reason itself.

Determination

At this large beast shelter in the Southeastern U.s.a., one in ten returning owners acquired an animal from the shelter post-obit return. The likelihood of post-return adoption was associated with the reasons for return and species. Individuals who returned animals for owner-related reasons were significantly less likely to adopt mail service-return compared with owners who returned due to creature-related reasons. However, owners who returned animals due to the animate being's wellness were iv times more than likely to adopt postal service-return compared with those who returned them for behavioral reasons. The experience of an unsuccessful fauna adoption appears to suppress an individual's desire to adopt again, especially when returns occur due to owner-related reasons or creature behavior. Futurity, prospective studies might investigate the utilize of alternative acquisition sources mail-render and elucidate possible differences in the experiences of people who prefer once more and those who do non.

Methods

Shelter characteristics

Charleston Animal Society is a large, open admission animate being shelter in South Carolina, U.s.a.. Between 2015 and 2019, the shelter'southward total alive intake included 17,664 dogs and 23,525 cats. About animals entered the shelter as strays, including 72% of dogs and 89% of cats. Charleston Animal Order employs an open adoption policy that aims to create a trusting and chatty relationship with adopters. The shelter encourages all adopters to render their animate being/s to the shelter if necessary and provides a refund voucher for future adoptions if the animal is returned within 30 days (excluding animals adopted during fee-waived promotions). Charleston Creature Society also offers mail service-adoption back up in the form of a free veterinarian appointment at a local veterinary clinic and complimentary behavioral support. The shelter'due south behavior team bear follow-up calls for animals with known behavioral problems in the shelter where possible, and adopters take the opportunity to contact the shelter to request behavioral advice and support if needed. The written report was determined exempt from review past the Academy of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board (protocol number 84837). The report was carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Information records and variables

Data from individuals who adopted and returned an brute to the Charleston Fauna Society between 1st January 2015 and 31st December 2019 were included in the study (n = 2073). Cases were excluded if the person's ID number differed betwixt the adoption and the return (n = 74). Data were downloaded from the shelter's electronic records (PetPoint Data Management System, Version 5, Pethealth Software Solutions Inc., USA) and the following variables were extracted: animal species, sexual activity, known/estimated date of birth, adoption date/s, return date/s and reason/s for return.

Beast shelter staff recorded a single return reason in PetPoint at the time of return. Researchers then categorized the render reasons into the post-obit groups: behavior, owner circumstances, health of owner, health of creature, housing, not compatible with children, not uniform with pets, non compatible with possessor, unrealistic expectations, unwanted and other (Table 1).

The creature's age at adoption was calculated as the number of months between the known/estimated date of nascency and the engagement of adoption. Adoption historic period was and then categorized every bit puppy/kitten (< half-dozen months), immature developed (> half-dozen months–2 years), adult (> 2–eight years) and senior (> 8 years). Length of stay in the home was calculated as the number of days between the adoption date and the return date. For owners who adopted post-return, the time betwixt return and post-return adoption was calculated as the number of days between the return date and the second animal's adoption date. A binary variable was created to compare individuals who adopted within 12 months of return and those who did non adopt inside 12 months. Twelve months was called as the cut-off value as this captured most individuals who adopted postal service-render while excluding outliers that may have adopted years later.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted in IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 24. A Pearson's Chi-Square examination was used to compare return reasons, and an contained t-test was used to compare the fourth dimension betwixt return and post-return adoption between dogs and cats. A binary logistic regression model was used to investigate the associations between mail service-render adoption (within 12 months) and the reasons for render, species (cats and dogs but), sex, length of stay in the home and age group of the returned brute. Returns due to 'insurance restrictions' (n = i) or 'abased by owner' (northward = 1) were excluded from the model due to the low number of cases. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Information availability

The data governance arrangements for the written report do non allow united states of america to redistribute Charleston Animal Order data to other parties.

References

-

American Veterinary Medical Association. AVMA Pet Ownership and Demographics Sourcebook: 2017–2018 Edition (2018).

-

Bir, C., Olynk Widmar, N. & Croney, C. Exploring social desirability bias in perceptions of dog adoption: All's well that ends well? Or does the method of adoption thing?. Animals 8, 154 (2018).

-

Bir, C., Widmar, N. J. O. & Croney, C. C. Stated preferences for canis familiaris characteristics and sources of acquisition. Animals seven, 59 (2017).

-

Garrison, Fifty. & Weiss, E. What practise people want? Factors people consider when acquiring dogs, the complexity of the choices they brand, and implications for nonhuman brute relocation programs. J. Appl. Anim. Welfare Sci. xviii, 57–73 (2015).

-

Marston, L. C., Bennett, P. C. & Coleman, G. J. Adopting shelter dogs: Owner experiences of the first month post-adoption. Anthrozoös 18, 358–378 (2005).

-

Mondelli, F. et al. The bond that never developed: Adoption and relinquishment of dogs in a rescue shelter. J. Appl. Anim. Welfare Sci. 7, 253–266 (2004).

-

Diesel, 1000., Pfeiffer, D. & Brodbelt, D. Factors affecting the success of rehoming dogs in the UK during 2005. Prev. Vet. Med. 84, 228–241 (2008).

-

Wells, D. L. & Hepper, P. G. Prevalence of behaviour problems reported past owners of dogs purchased from an animal rescue shelter. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 69, 55–65 (2000).

-

Kidd, A. H., Kidd, R. Yard. & George, C. C. Successful and unsuccessful pet adoptions. Psychol. Rep. 70, 547–561 (1992).

-

Patronek, G. J. & Crowe, A. Factors associated with high live release for dogs at a large, open-access, municipal shelter. Animals 8, 45 (2018).

-

Powell, L. et al. Characterizing unsuccessful animal adoptions: Historic period and breed predict the likelihood of render, reasons for return and mail service-render outcomes. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-87649-2 (2021).

-

Hawes, S. M., Kerrigan, J. Yard., Hupe, T. & Morris, Chiliad. N. Factors informing the return of adopted dogs and cats to an fauna shelter. Animals 10, 1573 (2020).

-

Casey, R. A., Vandenbussche, S., Bradshaw, J. W. & Roberts, 1000. A. Reasons for relinquishment and return of domestic cats (Felis silvestris catus) to rescue shelters in the UK. Anthrozoös 22, 347–358 (2009).

-

Stephen, J. G. & Ledger, R. A. An audit of behavioral indicators of poor welfare in kenneled dogs in the United Kingdom. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 8, 79–95 (2005).

-

Rooney, N. J., Gaines, S. A. & Bradshaw, J. W. Behavioural and glucocorticoid responses of dogs (Canis familiaris) to kennelling: Investigating mitigation of stress by prior habituation. Physiol. Behav. 92, 847–854 (2007).

-

Tanaka, A., Wagner, D. C., Kass, P. H. & Hurley, Chiliad. F. Associations among weight loss, stress, and upper respiratory tract infection in shelter cats. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 240, 570–576 (2012).

-

Kry, Grand. & Casey, R. The upshot of hiding enrichment on stress levels and behaviour of domestic cats (Felis sylvestris catus) in a shelter setting and the implications for adoption potential. Anim Welf. xvi, 375–383 (2007).

-

Jones, S. et al. Use of accelerometers to measure stress levels in shelter dogs. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 17, 18–28 (2014).

-

DiGiacomo, N., Arluke, A. & Patronek, G. Surrendering pets to shelters: The relinquisher'southward perspective. Anthrozoös 11, 41–51 (1998).

-

Shore, E. R. Returning a recently adopted companion beast: Adopters' reasons for and reactions to the failed adoption experience. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 8, 187–198 (2005).

-

González-Ramírez, One thousand. T. & Landero-Hernández, R. Pet–human relationships: Dogs versus cats. Animals 11, 2745 (2021).

-

Meyer, I. & Forkman, B. Dog and possessor characteristics affecting the domestic dog–owner relationship. J. Vet. Behav. nine, 143–150 (2014).

-

Herwijnen, I. R. V., van der Borg, J. A., Naguib, M. & Beerda, B. Dog ownership satisfaction determinants in the owner-canis familiaris relationship and the domestic dog's behaviour. PLoS One 13, e0204592 (2018).

-

Buller, K. & Ballantyne, 1000. C. Living with and loving a pet with behavioral problems: Pet owners' experiences. J. Vet. Behav. 37, 41–47 (2020).

-

González-Ramírez, M. T., Vanegas-Farfano, M. & Landero-Hernández, R. Differences in stress and happiness between owners who perceive their dogs as well behaved or poorly behaved when they are left alone. J. Vet. Behav. 28, one–v (2018).

-

George, R. Due south., Jones, B., Spicer, J. & Budge, R. C. Health correlates of compatibility and zipper in human-companion beast relationships. Soc. Anim. half dozen, 219–234 (1998).

-

Curb, L. A., Abramson, C. I., Grice, J. Westward. & Kennison, Due south. M. The relationship between personality match and pet satisfaction amongst dog owners. Anthrozoös 26, 395–404 (2013).

-

González-Ramírez, K. T. Compatibility betwixt humans and their dogs: Benefits for both. Animals 9, 674 (2019).

-

Belshaw, Z., Dean, R. & Asher, L. "You can be blind because of loving them so much": The impact on owners in the U.k. of living with a dog with osteoarthritis. BMC Vet. Res. 16, 1–10 (2020).

-

Spitznagel, Thousand. B. & Carlson, Chiliad. D. Caregiver brunt and veterinarian client well-being. Vet. Clin. Small Anim. Pract. 49, 431–444 (2019).

-

Spitznagel, M. B. et al. Caregiver burden in the veterinary dermatology client: Comparison to healthy controls and relationship to quality of life. Vet. Dermatol. xxx, three-e2 (2019).

-

Reese, L. A. Brand me a match: Prevalence and outcomes associated with matching programs in canis familiaris adoptions. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 24, 1–13 (2020).

-

Powell, 50. et al. Expectations for dog ownership: Perceived physical, mental and psychosocial health consequences among prospective adopters. PLoS ONE 13, e0200276 (2018).

-

O'Connor, R., Coe, J. B., Niel, L. & Jones-Bitton, A. Effect of adopters' lifestyles and beast-care knowledge on their expectations prior to companion-brute guardianship. J. Appl. Anim. Welfare Sci. xix, 157–170 (2016).

-

O'Connor, R., Coe, J. B., Niel, L. & Jones-Bitton, A. Exploratory study of adopters' concerns prior to acquiring dogs or cats from animal shelters. Soc. Anim. 25, 362–383 (2017).

-

Notari, Fifty. & Gallicchio, B. Owners' perceptions of behavior bug and behavior therapists in Italy: A preliminary study. J. Vet. Behav. 3, 52–58 (2008).

-

Kirk, C. P. Dogs have masters, cats have staff: Consumers' psychological ownership and their economic valuation of pets. J. Coach. Res. 99, 306–318 (2019).

-

Segurson, S. A., Serpell, J. A. & Hart, B. L. Evaluation of a behavioral cess questionnaire for use in the characterization of behavioral problems of dogs relinquished to creature shelters. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 227, 1755–1761 (2005).

-

Stephen, J. & Ledger, R. Relinquishing domestic dog owners' ability to predict behavioural problems in shelter dogs postal service adoption. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 107, 88–99 (2007).

-

Tami, G. & Gallagher, A. Description of the behaviour of domestic domestic dog (Canis familiaris) past experienced and inexperienced people. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 120, 159–169 (2009).

-

Mariti, C. et al. Perception of dogs' stress past their owners. J. Vet. Behav. 7, 213–219 (2012).

-

Kerswell, 1000. J., Bennett, P. J., Butler, K. Fifty. & Hemsworth, P. H. Cocky-reported comprehension ratings of dog behavior by puppy owners. Anthrozoös 22, 183–193 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We thank Charleston Animal Society for providing their support, expertise, and data throughout this written report. We too thank the Bernice Barbour Foundation for their support of Penn Vet Shelter Medicine Programme faculty and the Arnall Family Foundation for their support of the program mail service-doctoral researcher.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.P., C.L.R., B. West. and J.S. conceived and designed the written report. D.S. and G.M. provided the original data. L.P. extracted the data, performed the data analyses, and drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read and approved the submitted manuscript.

Respective author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

D.South. and M.One thousand. are paid employees of Charleston Animal Club. Charleston Animal Society did non fund this research or contribute to the study pattern, data assay or initial drafting of the manuscript. Bacon for C.L.R. was provided by grant funding from the Bernice Barbour Foundation, and salary for 50.P. was provided by grant funding from the Arnall Family unit Foundation. The other authors declare no other competing interests.

Additional data

Publisher'due south note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Artistic Commons Attribution four.0 International License, which permits employ, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you lot give advisable credit to the original author(southward) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and signal if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Eatables licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the textile. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended employ is not permitted past statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/four.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Powell, L., Reinhard, C.L., Satriale, D. et al. The impact of returning a pet to the shelter on futurity animal adoptions. Sci Rep 12, 1109 (2022). https://doi.org/x.1038/s41598-022-05101-5

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-05101-five

Comments

Past submitting a annotate you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If yous find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it equally inappropriate.

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-022-05101-5

Posted by: lomaxbuting.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Can You Return An Animal To A Shelther"

Post a Comment